Queer representation in cinema has a long and complicated history and no more so than in the horror genre. So intertwined is the horror genre with queer identity that Chad Collins of Dread Central has declared: “The History of Horror is the History of Queerness.”

The roots of horror go back to the Gothic novels, a literary genre pioneered by various queer writers with notable works such as Matthew Lewis’s The Monk (1796), Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, Sheridan Le Fanu’s lesbian vampire novella Carmilla (1872), and Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890). Outside of Frankenstein, the most influential of these gothic novels on horror films is arguably Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897), a novel written by the closeted gay writer in response to witnessing his close friend Oscar Wilde sentenced to hard labour for sodomy.

ALL VAMPIRES ARE GAY: SUBVERTING THE CODE

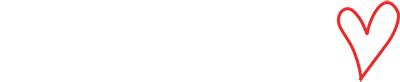

As writer Richard Primuth explains: “In a time of extreme repression and fear for gay people, using their vampire characters as a metaphor for their own hidden sexuality was an outlet for self-expression” (Vampires Are Us, The Gay & Lesbian Review/Worldwide). Case in point: Dracula was not the first vampire story, outside of folklore, committed to print. That would be 1819’s The Vampyre, the short story written by John William Polidori as part of the infamous ‘friendly’ writing contest between himself, Mary Shelley, Lord Byron, and Percy Shelley: an event that has been portrayed in several films including the psychological horror film Gothic (1986), the drama Haunted Summer (1988), the biopic Mary Shelley (2017), and even alluded to in definitive monster film The Bride of Frankenstein (1931).

While The Vampyre is considered the progenitor the romantic vampire genre and fantasy fiction, it is more infamously known as being a blind item hit-piece about the very queer and charismatic Lord Byron, who it has been suggested Polidori had been infatuated with and rebuffed by (see Poor Polidori: The Toxic Relationship that Inspired The First Vampire Story). All it took was one gay grudge to inspire an entire genre that traverses all mediums including screen content. After The Vampyre’s publication (that had been falsely attributed to Lord Byron as the author), a ‘vampire craze’ swept Europe, spawning countless tales from operas, novels, and within one hundred and three years from its first publication: the classic monster movie.

Published seventy-eight years after Polidori’s The Vampyre, Bram Stoker’s Dracula has been adapted for film, television, video, games and animation over seven hundred times, with many more theatrical and comic book adaptations. The first sound film adaptation is 1931’s film, Dracula that starred Bela Lugosi who immortalized the role in its many sequels and spin-offs. Directed by Tod Browning (a gay man), the film also boasts being the first sound talkie horror picture. In How Horror Thwarted ‘The Code,’ Elizabeth Erwin writes of the history of horror films pushing the boundaries during the Hays code under the purview of the National Legion of Decency (LOD), which was affiliated with the United States Roman Catholic Church: “The relationship between the title character in Dracula and his manservant Renfield contains a homoerotic subtext designed to make Dracula even more menacing in the minds of the audience. His enslavement of Renfield has a sadomasochistic quality but skirts the LOD’s injunction against displays of perversion due largely to Renfield’s depiction as an effeminate, sarcastic foil…. These cinematic moments also served to place members of the LOD board in a difficult position. Because the sexuality being projected was not overt, admitting that you were picking up a homosexual vibe in such a movie could arouse suspicion among your colleagues.”

The renewed enforcement of the Hays Code by the mid-30s saw filmmakers bending to the code’s will or finding new ways to subvert it. 1936’s Dracula’s Daughter was a sequel to the 1931 film but has been considered by film critics and historians more of a loose adaptation of the novel Carmilla, and is the first feature film to hint at a lesbian in a vampire film. The story is of Countess Marya Zaleska who is seeking a cure for her lesbianism—er, vampirism—through psychiatry, reinforcing the association between homosexuality and mental illness (it is important to note, that filmmakers weren’t pulling this mental illness association with queerness from thin air as homosexuality was considered a mental illness by the American Psychiatric Association until finally being removed as a diagnosis from the DSM in 1973). Erwin writes: “Lesbian monsters were crafted to evoke pity…. Rather than making a woman an active participant in her lesbianism, and thus inciting the ire of the LOD, coding enabled the woman to be victimized by a nameless disease that, to a queer audience, would easily be read as homosexuality.”

Gloria Holden’s performance of Dracula’s daughter has been described by writer Gary Morris as having: “almost single-handedly redefined the ‘20s movie vamp as an impressive Euro-butch dyke bloodsucker,” (see Queer Horror: Decoding Universal’s Monsters, Bright Lights Film Journal) with Anne Rice later attributing Holden’s role as a major source of inspiration in writing the homoerotic gothic horror, Interview with A Vampire (1976) particularly in its treatment of Louis de Pointe du Lac as ‘the regretful vampire’ (Anne Rice and The Making of A Modern Vampire, Sublime Horror).

While the Hays Code dictated the ‘mores’ in film until its abandonment in the late 60s, it did not extend to the publishing industry where in the mid-twentieth century lesbian pulp fiction flourished and managed to evade censure even after the House Select Committee on Current Pornographic Materials asserted the genre “largely degenerated into media for the dissemination of artful appeals to sensuality, immorality, filth, perversion, and degeneracy,” in its 1953 report. Of special target of criticism by the committee was pulp fiction cover art, described as “lurid and daring illustrations of voluptuous young women on the covers of the books” (Pulp’s Big Moment, The New Yorker). When the Hays Code lifted in 1968, both the contents and cover art of lesbian pulp fiction went on to influence the aesthetic of queer campy horror films, particularly those by Hammer Films Productions (a British production company known for its staple of schlocky horror in the 50s and 60s and into the 70s).

As censorship was being relaxed in both the UK and the States, Hammer Studios decided to adapt the gothic horror novel Carmilla as a means to get past the British Board of Film Censors warnings against depictions of lesbians by making the argument that the lesbianism was present and intrinsic to the original source material (by then a classic book in the literary canon). Rather than tone down the source material, Hammer decided “it would take another stab at sensationalism by upping the violence quotient and, for the first time, adding lots of explicit nudity into the mix.” The film was titled The Vampire Lovers and released in 1970. Writer Max Evry comments that it took the films “potent combination of explicit nudity and sexuality paired with the sumptuous production values of Hammer to usher in a bold new era exploring the true subtext of all vampire lore.” The Vampire Lovers would go on to spawn two sequels (the campy lesbian vampire films Lust for a Vampire and Twins of Evil) and also heavily influence the film The Hunger, starring Susan Sarandon and Catherine Deneuve, released a decade later (Year Of The Vampire: The Vampire Lovers Brought Sexy Back To Bloodsucker Lore, Slash Film).

Meanwhile, the film adaptation for Anne Rice’s Interview with A Vampire (published eight years after the end of the Hays Code), would languish in development hell until the 1994 movie starring Tom Cruise and Brad Pitt. The smash box office hit was directed by Neil Patrick Jordan who was flying high after his sleeper success with 1992’s The Crying Game, which won an Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay (and has its own complicated legacy in queer cinema). Hollywood was, by this time, beginning to bank on queer characters with more positive representation aimed at mainstream audiences even if that representation was still heavily coded. This is exemplified by Joel Schumacher’s The Lost Boys (described by The British Film Institute as a ‘hedonistic party vamps” that offers up “a whole host of gay pleasures”) released only a few years prior to Interview with A Vampire in 1987. For both films, the homoeroticism (although considered risqué at the time) is fairly muted in comparisons to Rice’s novels and even by today’s standards.

THE MONSTER IS DEGENERATE: SUBVERTING AND INCITING MORAL PANIC

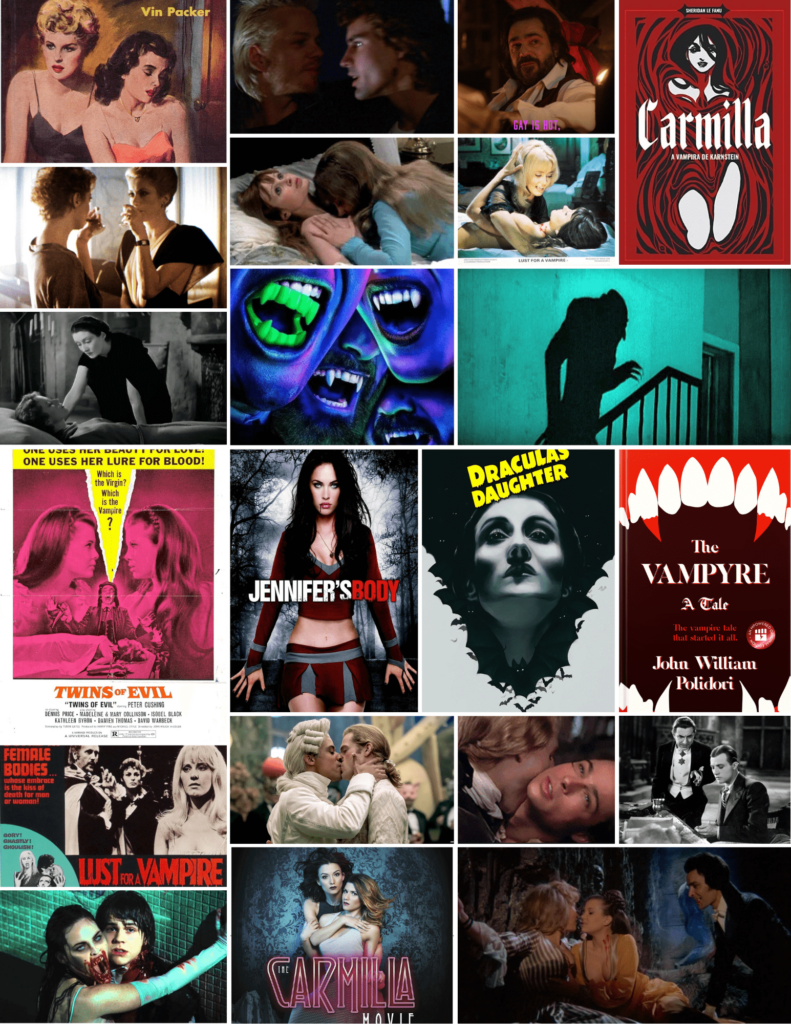

Director James Whale (who was one of the few openly gay men working throughout his career in Hollywood) had been originally set to direct Dracula’s Daughter following the success of his films Frankenstein (1931) and The Bride of Frankenstein (1935), but that fell through. A sequel to the smash hit Frankenstein, starring Boris Karloff, The Bride of Frankenstein has been described as ‘a campy masterpiece’ that ‘almost demands to be treated as one of the historical high-water marks of sexual subversion’ (see Gary Morris’s Sexual Subversion: The Bride of Frankenstein, Bright Lights Film). The film, full of gay subtext, ‘teems with homosexual presences behind and before the camera,’ with major characters played by gay and bisexual men and also starring Elsa Lanchester who was married to Charles Laughton (a noted bisexual). In the film, Lanchester plays both the historical Mary Shelley and the fictional monstrous Bride, who, on rejecting her intended husband instantly cemented the character (with her signature updo hair with streaks of lightning bolts on either side) as both a lesbian and future drag queen icon.

But the queering of characters didn’t stop with the Bride. Gary Morris goes on to observe that the characters Doctor Pretorius and Doctor Frankenstein work “together to ‘give birth’ to a woman, two homosexuals replacing the heterosexual model of male and female parenting and replacing God—annihilating those noxious enemies of homosexuality, society and religion, in one blow.” This theme of would later be pushed further by the character of Dr. Frank N. Furter (played by Tim Curry in 1975’s campy horror musical The Rocky Horror Picture Show),who is coded ‘queer by all meanings of the word for his plot to create the perfect man to serve all of his sexual and murderous desires’ (10 of the Best Queer Characters From Horror Movies, Shows and Games, Collider). The Monster from The Bride of Frankenstein is likewise coded gay, with writer Carson Timar commenting: “The Monster is a character cursed by its taboo nature. Seen as something unnatural that goes against the correct order of life, everyone turns against The Monster and attacks him for his taboo identity within society…. Where the movie has its iconic monsters, it makes it clear that the true horror is the society which tears them down and even leads The Monster to commit suicide at the end” (The Haunting Queer Reading of The Bride of Frankenstein, Filmotomy).

While James Whale’s film can be read to assert that the coded-homophobic mobs are the real monsters, some queer films, even those who were made by queer filmmakers, can be seen as inciting moral panic. Before Universal Pictures cemented the classic monster movie genre with both Frankenstein and Dracula in the early ‘30s, the first widely-known vampire film is the German Expressionist silent film Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror (a 1922 unofficial adaptation of the Bram Stoker’s Dracula). Tapping into the social and sexual anxieties of 1920’s Germany, the director F.W. Murnau ‘used Nosferatu as an allegory for the male fears of women’s liberation, the blatant expression of queerness, and the growing xenophobia surrounding Eastern immigrants and the Jewish people’ (see: How Nosferatu Director F.W. Murnau Queered The Cinematic Vampire Forever by BJ Colangelo).

Although a gay man himself, Murnau’s portrayal of the vampire Count Orlok was situated firmly within a European/Christian anti-Semitic legacy that associated Jews, in folklore, with both vampires and sexual deviance going back thousands of years. Writer Chloe Hyman likens Hitler’s later blaming Jewish and queer people for spreading syphilis and ‘degeneration’ (a few years shortly after the release of Nosferatu) to the same media discourse later seen towards queers during the AIDS crisis: ‘The media likened queer people to monsters and serial killers on account of their alleged threat to public health, the sacred family unit, and the spiritual health of the nation’ (see: Specters of Queer Trauma in Nosferatu, The Vampyr).

However, just prior to the dawn of the AIDs epidemic, several major Hollywood thrillers had been already released that fed into this queer panic and blatant homophobia, with three films released in 1980 alone (within months after the assassination of Harvey Milk): William Friedkin’s Cruising, Brian De Palma’s Dressed to Kill, and Gordon Willis’s Windows. All three are described as ‘sleazy metropolitan nightmares, with naive heterosexuals terrorised by the queer unknown.’ Like Nosferatu did during 1920’s Germany, these films fed into the social anxieties of conservative America in a backlash against growing gay rights movement when ‘the idea of queer equality was at the time so frightening.’ (see: Adam White’s Scream Queens: Remembering The Short-Lived Queer Villains of Horror, The Independent).

Five years later, the slasher film A Nightmare on Elm Street 2: Freddy’s Revenge (1985) would push the boundaries in exploring homoerotic themes and has since enjoyed a gay cult film following. This despite the intent at the time by the film’s writer, David Chaskin, who has since admitted: “Homophobia was skyrocketing and I began to think about our core audience—adolescent boys—and how all of this stuff might be trickling down into their psyches… My thought was that tapping into that angst would give an extra edge to the horror.” (The Nightmare Behind The Gayest Horror Film Ever Made, Buzzfeed).

The legacy of this moral panic towards the LGBTQIA+ community during the Reagan era has cast a long shadow in film. De Palma’s Dressed to Kill, which ‘reduced transgender identity to a kind of split-personality disorder’, was seen as recently as 2016 in M. Night Shyamalan’s horror film Split. That film featured James McAvoy as Kevin Wendall Crumb, a villain with 24 split personalities (including Patricia who wears women’s clothes and a literal demon with supernatural powers called The Beast), who kidnaps three teenage girls and keeps them locked in an underground room. The film was blasted for perpetuating ‘the trope of the ‘dangerous, perverted transsexual’ and for implying ‘that people who are assigned male at birth but don feminine clothes are evil and dangerous’ particularly at a time when US anti-trans legislation was gearing up to prevent trans people from using restrooms of their gender identity (see Roe McDermott’s On Transphobia in Film, and Sex as Sinful, Dublin Inquirer).

THE BIRTH OF THE QUEER SLASHER

Dressed to Kill was certainly not the first to conflate queer sexuality and identity with mental illness and/or mental illness with villainy in horror as already discussed with Dracula’s Daughter. The most famous example in film would be Alfred Hitchcock’s masterpiece Psycho (1960) in which its villain Norman Bates, played by Anthony Perkins, is “a fey murderer who dresses up as his dead mother, was a gay, Freudian nightmare” (Adam White). Psycho would not be Hitchcock’s first or last foray in featuring queer subtext and queer characters and he was known to often collaborate with queer writers and performers on his films (Rebecca, Suspicion, Rope, and Strangers on a Train to name a few). Writer Christian Blauvelt observes of Psycho: “The remarkable thing about all this is that Hitchcock makes you identify with Perkins (who was gay and closeted in real life) as much as he did Marion Crane herself, to the point that, as Hitchcock often did at his perverse best, you’re kinda rooting for him…. In making you relate to an identity-fluid character… perhaps Hitchcock was attempting the queering of the audience this time as well” (24 Famously Queer and Homoerotic Horror Movies, from ‘Psycho’ to ‘Hellraiser’, IndieWire).

Psycho had a major influence on later ‘60s horror films including those produced by Hammer Studios and the later slasher films of the ‘70s and ‘80s (that were also inspired by ‘60s’ Italian splatter films and problematic exploitation films). The British Film Institute has described the slasher this way: “With the finesse of a blade piercing through taut skin, the horror film is all about slicing up conventions and destroying the status quo. Taking a bloody axe to the bloodcurdling confines of tradition, there is something fundamentally queer about the horror genre,” (Scream Queens: Gay Boys and the Horror Film, BFI).

While A Nightmare on Elm Street 2: Freddy’s Revenge has a problematic legacy to contend with other slasher films of the time were much more progressive. 1981’s Butcher, Baker, Nightmare Maker (rereleased as Night Warning) is a film noted for being an early example of positive representation of a gay man. In an on-camera interview for the independent grindhouse production company Code Red, actor Steve Easton, who played Tom Landers (the gay basketball coach of the film’s lead character Billy) said: “He’s a gay man, but he’s not a pervert. He just likes men, and he’s got a boyfriend, and his boyfriend is murdered.” This film would also push ‘the real monster is the homophobic mob’ theme (as first hinted at in The Bride of Frankenstein) by placing the knife of the slasher directly into Billy’s homophobic aunt’s hands as she bemoans “Homosexuals are very, very sick!” during her killing spree throughout the film.

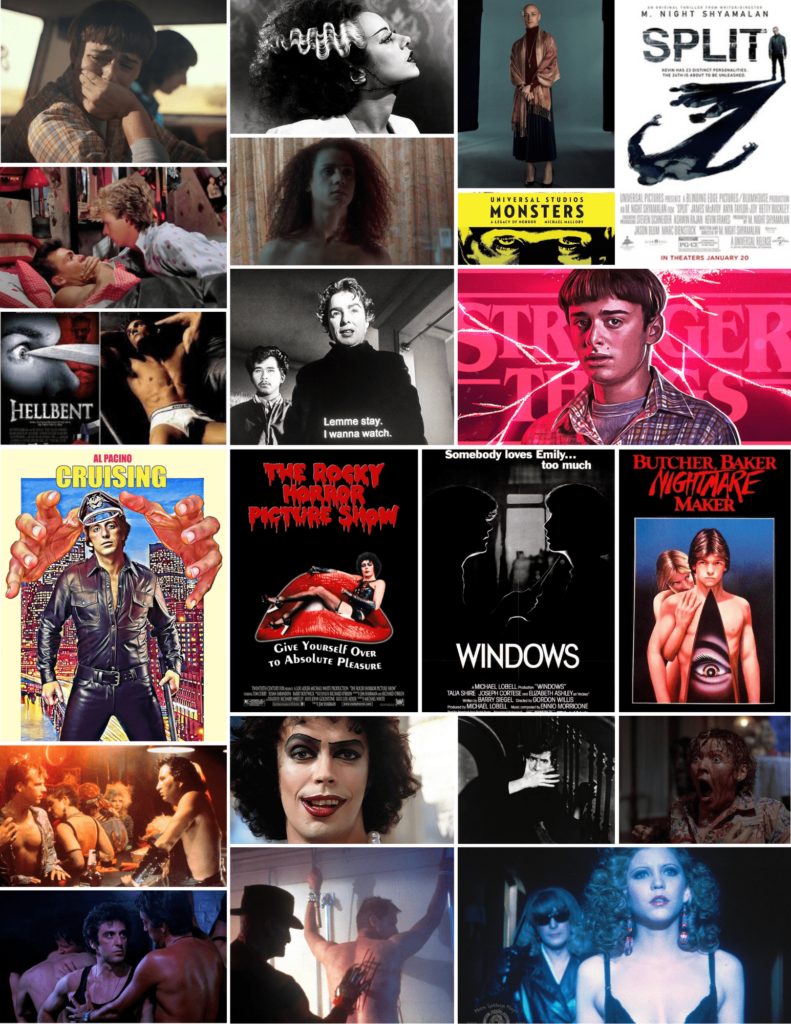

By the time the 2004 movie Hellbent was released, the AIDs Panic of the 80s and 90s had begun to subside, the gay rights movement grew more ground, and more and more horror films that portrayed queer characters in a positive light had been since released. What makes Hellbent stand out as a slasher was that it was the first to get a theatrical release starring gay characters ‘in a world where being LGBTQ+ is the norm and not the exception’ (The Queer World of ‘Hellbent’, Dread Central). The film would go on to spark a wave of gay slasher films in the later aughts and into the teens and twenties with no signs of slowing down with films like Knife + Heart (2018), Killer Unicorn (2018), Midnight Kiss (2019), The Retreat (2021), and Fear Street Trilogy (2021) released in the last five years.

RE-ENVISIONING QUEER HORROR IN THE 2000s

Just over 200 years after Polidori’s initial publication of The Vampyre, the much lauded AMC TV adaptation of Interview with A Vampire was launched in 2022. Finally, the vampire is no longer coded gay, but gay as fuck. As the showrunner Rolin Jones has stated on numerous occasions: they have made the subtext of the books the text of the series (How AMC’s Interview with the Vampire Changes the Anne Rice Books, Den of Geek). With the growing acceptance of LGBTQ+ communities, previous problematic queer horror films are being revisited, re-visioned, and course-corrected with out loud and proud sensibilities. Series like Bates Motel (2013-2017), a ‘prequel’ to Psycho, and Chucky are able to dive deeper into the nuances and complexities of their queer characters than in previous eras. The Netflix series Stranger Things (its later seasons heavily influenced by the Nightmare on Elm Street franchise), set in the ‘80s, portrays gay and lesbian characters in a positive light (who, yes, still have to contend with the homophobia of the day). It will be interesting to see where the series takes the now admittedly gay teenage character of Will in season five in a period set when the AIDS epidemic ramps up (the fourth season took place in March 1986).

And thanks to films like Jennifer’s Body (2009), What We do in The Shadows (2014), and Bodies Bodies Bodies (2022), queer horror comedy is a now a thriving sub-genre both in film and TV. Psst…be sure to check out Sloppy Jones on OutTV.

For more on the history of queer horror check out the docuseries Queer for Fear: The History of Queer Horror (2022) on Shudder.

The History of Pride

The History of Pride

Leave a Reply